Do you remember the 2016 viral photo of an octopus swimming next to parked cars in a flooded Miami parking garage? A particularly high tide had likely pushed the unsuspecting creature through a drain pipe and into alien territory. For Rob Verchick, climate law scholar, it was a clear sign of climate change—and a preview of how humans might need to adapt.

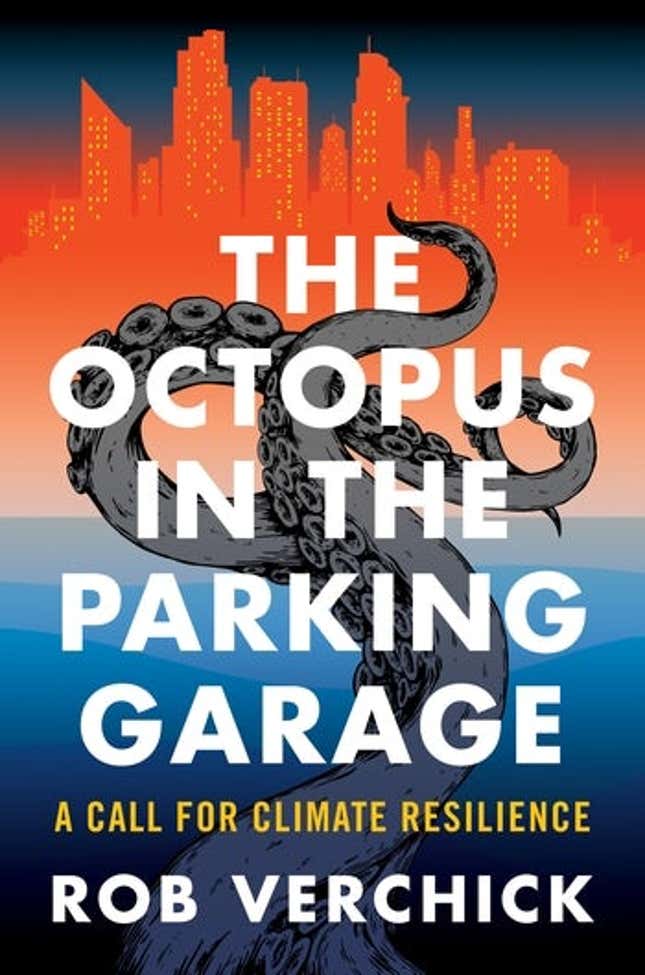

When those drainage pipes were first installed, they were above the water line. But after years of sea level rise, the waterline began to encroach farther and farther inland. That octopus and parking lot became the perfect anecdote to open Verchick’s new book, The Octopus in the Parking Garage: A Call for Climate Resilience, out April 2023.

I spoke to Verchick about his book and his thoughts on humanity’s approach to this existential threat. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Angely Mercado, Earther: Why is the octopus the through line for resilience in the book?

Rob Verchick: Well, it’s funny. When that octopus was found in the parking garage, my friend Dan Farber, who’s a professor at Berkeley, sent me a news article about it. And I was like, “did this really happen, was this really true?” We quickly realized that it had something to do with the climate. That was one of the contributing factors to making the water reverse and pushing that octopus into the garage. Dan and I actually decided that we were going to write an op-ed for the Miami Herald, using the octopus as a symbol of climate change and an eight-armed alarm bell for climate resilience.

We used octopus as a stand-in for the elephant in the room. The more I thought about it, the more I thought, ‘that might be a nice entry into a book aimed at a lay audience.’ I was looking for a symbol that wasn’t immediately scary. If you start talking about wildfires and houses being blown away by hurricanes, that sets a mood and it creates anxiety. The book that I wanted to write was about introducing people to a topic and getting them to think about it in terms of solving a practical problem. So they could feel empowered, as maybe part of the solution.

Earther: So we’re the octopus, because we’re affected by climate but have to float along somehow.

Verchick: I had to learn more and more about octopuses. I called biologists and started doing my own reading. I realized that octopuses are really very special creatures, and they have evolved to adapt to many kinds of situations. They only live about a year, well, most of them. And so, in that year, there’s a lot of learning that takes place. They have to learn all kinds of things about what kinds of foods to eat, where to find it, how to hide, how to protect themselves. I thought, well, that’s what human beings are like, too. That’s our calling card as a species. We’re not particularly good at any one particular thing. We don’t run the fastest. But what we are really good at is adapting.

We’re really good at forming networks. The problem with that is that, although we’re really good at adapting in positive ways, we’re also really good at endangering our own environment. Octopuses… they change their colors, they can pour themselves almost liquid-like into different kinds of spaces underwater. We have to be flexible like that.

Earther: You highlighted that flexibility with your Hurricane Katrina experience in the book. Why did you stay in NOLA when so many people left?

Verchick: That question is an experience everyone in my city has gone through. I moved to New Orleans in 2004, nine months before Hurricane Katrina. We came here and then, nine months later, the house was under probably 6 to 8 feet of water for about five weeks.

My wife and kids were lucky enough to stay with family in Washington state, and I stuck around this region to figure out what we were going to do. We had a family meeting about it, and we decided that we were going to stay. There is something so special about this city and its culture. I’m very grateful to have the ability to be able to contribute.

Earther: You end the book visiting a national park to see a melting glacier, and you describe witnessing climate change. Why is that important?

Verchick: It’s actually the first thing that I wrote for the book, and I knew it was going in there. It is what really inspired me. That is a glacier that I had seen over the years, hundreds of times, and it’s changing. That was something that I could say is causing me to notice. For someone else, that might be a coral reef, for someone else it might be your kids’ asthma. That’s why there’s the chapter about a woman whose son has allergies. And they get worse during wildfire season when smoke drifts into Las Vegas. Her being attentive to that and noticing that leads her to make connections. She is now in climate resilience work.

Earther: Why and how should people become climate witnesses?

Verchick: In the very beginning of the book, there is an interview that I have with Kathleen Sealey, who is a marine biologist and teaches at the University of Miami about climate and land use. In the book, she assigns her students the work of keeping a journal noticing how the environment is changing over time. Because noticing and understanding and being the witness is the first part of the action. And sometimes it’s hard, right, sometimes it’s emotionally draining. But the only way you can solve a problem is to first of all understand what the problem is.

Want more climate and environment stories? Check out Earther’s guides to decarbonizing your home, divesting from fossil fuels, packing a disaster go bag, and overcoming climate dread. And don’t miss our coverage of the latest IPCC climate report, the future of carbon dioxide removal, and the invasive plants you should rip to shreds.