We need climate action. But just because something gets grouped under the umbrella of things that theoretically combat climate change doesn’t mean it’s actually good for the planet or people. In an alarming example, production of certain alternative “climate-friendly” fuels could lead to dangerous, cancer-causing emissions.

A Chevron scheme to make new plastic-based fuels, approved by the Environmental Protection Agency, could carry a 1-in-4 lifetime cancer risk for residents near the company’s refinery in Pascagoula, Mississippi. A February joint report from ProPublica and the Guardian brought the problem to light. Now, a community group is fighting back against the plan, suing the EPA for approving it in the first place, as first reported by ProPublica and the Guardian in a follow-up report on Tuesday.

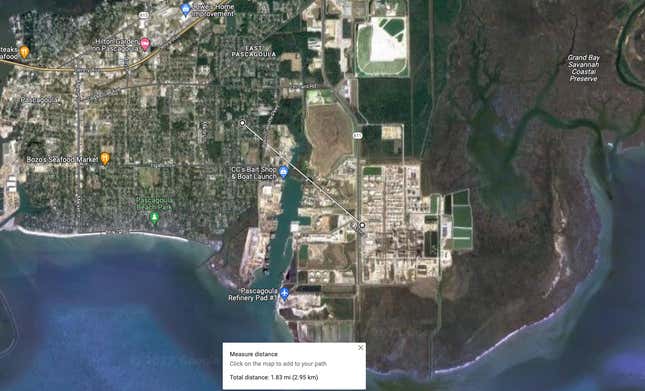

Cherokee Concerned Citizens, an organization that represents a ~130 home subdivision less than two miles away from Chevron’s Pascagoula refinery, filed its suit to the Washington D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals on April 7. The petition demands that the court review and re-visit the EPA’s rubber stamp of the Chevron proposal.

U.S. Senator Jeff Merkley also sent a letter to EPA administrator, Michael Regan, last week decrying his agency’s decision and requesting more information by April 30. Citing the February ProPublica and Guardian report, Merkley wrote that he found the EPA/Chevron approval “especially troubling,”

“I am concerned...that the EPA’s program...is resulting in significant increased toxic chemical exposure to frontline communities,” he added.

Cherokee Concerned Citizens represents a community already beset by the consequences of industrial pollution. An earlier 2021 ProPublica investigation deemed parts of Pascagoula, Mississippi a cancer hotspot because of the toxins released from Chevron’s refinery and other nearby facilities including a Rolls Royce factory that manufactures equipment for the U.S. Navy and a chemical plant.

One resident, and a co-founder of Cherokee Concerned Citizens, Barbara Weckesser, told ProPublica and The Guardian that five of her neighbors are currently in chemotherapy treatment. When she first read the news about Chevron’s plan, Weckesser told the outlets she was shocked by the numbers. But in other ways, not so shocked. “Here we go again,” she thought.

What did the EPA Approve and Why?

Last year, the EPA greenlit Chevron’s plan to emit some unnamed, truly gnarly, cancer-causing chemicals at a refinery in Pascagoula. The approval fell under an effort described as fast tracking the review of “climate-friendly new chemicals.” Chevron proposed turning plastics into novel fuels, and the EPA hopped on board, in accordance with a Biden Administration policy to prioritize developing replacements for standard fossil fuels.

By opting to “streamline the review” of certain alternative fuels, the agency wrote it could help “displace current, higher greenhouse gas emitting transportation fuels,” in a January 2022 press release. But also, through that “streamlining,” the EPA appears to have pushed aside some major concerns.

In the same document where the agency authorizes Chevron to produce the list of new compounds, the EPA also notes “the manufacture, processing, distribution in commerce, use, or disposal of these New Chemical Substances may present an unreasonable risk of injury to health or the environment.” Specifically, the agency determined that smokestack emissions from one chemical, dubbed P-21-0158, could carry a 1-in-4 lifetime cancer risk for people living nearby. In other words: One out of every four residents living near the Chevron refinery, exposed to P-21-0158's byproducts in the air would be expected to develop cancer.

That 1-in-4 risk is about 250,000 times higher than the 1-in-1 million acceptable cancer risk threshold that the EPA generally applies when considering harm to the public. Another chemical listed in the approval document as P-21-0150 carries a lifetime cancer risk estimate of 1-in-8,333 for those exposed to fugitive air emissions —also far above the EPA’s acceptable risk threshold. The agency further notes certain chemicals included in Chevron’s plans could potentially pose an increased cancer risk through groundwater or via fish ingestion. The EPA classified 11 of the total compounds discussed as a “high environmental hazard.” For individual workers exposed to these chemicals more directly during production, at least one compound carries an estimated cancer risk of 1-in-140—greater than 70x the agency’s acceptable occupational risk threshold of 1-in-10,000.

For some reason though, despite its own internal risk cut-offs and federal regulation surrounding new chemical approvals, the EPA allowed Chevron to move forward without any further testing or a clear mitigation plan in place.

It’s hard to say, specifically, what these EPA-approved compounds are because in the single relevant agency document obtained by ProPublica and the Guardian, chemical names are blacked out. However, the substances in question are all plastic-based fuels, as outlined in another, related document. Though obtuse, their approval seems to stem from a recently renewed national program to promote biofuel development, through a loophole that allows for fuels derived from waste.

Actual biofuels, derived from plants or organic matter, can be environmentally problematic and controversial in their own right. But plastics-based fuels are a whole separate beast. For one, they’re not actually “climate-friendly” considering plastic is still a petroleum product derived from fossil fuels. And two: Burning plastic and its derivatives still releases greenhouse gases.

Nonetheless, the Biden Administration’s push for more “biofuels” and re-upped Renewable Fuel Standard makes wide allowances for any fuel source that comes from trash—apparently regardless of the possible fallout.

What do Chevron and the EPA say?

Gizmodo reached out to the EPA and Chevron for more information, but didn’t receive responses by publication time.

To ProPublica and The Guardian, Chevron spokesperson Ross Allen said, “It is incorrect to say there is a 1-in-4 cancer risk from smokestack emissions,” but offered little in the way of alternative interpretations back in February. An EPA spokesperson told the outlets in February that the 1-in-4 risk was a “very conservative estimate with ‘high uncertainty.’”

More recently, Chevron has released an entire FAQ page dedicated to assuaging Pascagoula locals’ concerns. The site notes that the 1-in-4 cancer risk is “based on EPA’s initial risk screening,” and claims that such an assessment doesn’t “doesn’t reflect how it would actually be done.”

“We will not do anything that is unsafe for our workers or our neighboring communities. We will ensure it can be done safely or not at all,” Chevron says on that page. But those statement don’t exactly square with the company’s track record.

Chevron’s Pascagoula Refinery has failed to comply with EPA-imposed emissions limits and violated safety regulations in the past. In 2018, Chevron had to pay millions of dollars in penalties and spend about $150 million on fixes following a Department of Justice settlement related to alleged Clean Air Act violations in Mississippi.

The recently approved chemicals aren’t covered by the Clean Air Act, which only applies to a short list of pollutants. But still, Cherokee Concerned Citizens has made it clear people living near the refinery don’t want to breathe them in.